Styron Visible: Naming the Evils That Humans Do

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

Published: November 3, 2006

At a time when many of his contemporaries were documenting the domestic travails of middle-class suburban life, or excavating the geological layers of their own psyches, William Styron — who died of pneumonia Wednesday at 81 — was boldly tackling the big, unwieldy themes of crime and punishment and redemption, and creating big-boned dramatic narratives set against the great conflagrations of history: slavery in “The Confessions of Nat Turner” and the Nazi death camps in “Sophie’s Choice.”

Ivan Croscenco/Associated Press

William Styron in his library at his home in Rome, 1960, shortly after publication of “Set This House on Fire.”

Worldly Words

William Styron, who died Wednesday of pneumonia at 81, married grand historical themes with his own fraught life as a Southern writer who struggled with depression. Below is a bibliography (with links to reviews where available).

Lie Down in Darkness (1951)

The Long March (1956)

Set This House on Fire (1960)

The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967)

Sophie's Choice (1979)

This Quiet Dust, and Other Writings (1982)

Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness (1990)

A Tidewater Morning: Three Tales From Youth (1993)

Interviews

David Dempsey Interviews Styron (1951)

George Plimpton Interviews Styron (1967)

Readers’ Opinions

Forum: Book News and Reviews

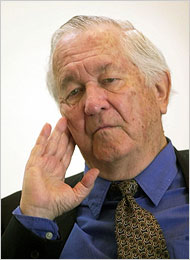

Alexa Welch Edlund/Richmond Times-Dispatch, via Associated Press, 2000

“Human beings are a hair’s breadth away from catastrophe at all times.”

It was a tropism that stemmed in part from Mr. Styron’s appreciation for the gravity and swoop of the great modern writers of tragedy like Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Thomas Mann — his conviction, in Herman Melville’s words, that “to produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme”; and in part from his own belief that “human beings are a hair’s breadth away from catastrophe at all times — both personally and on a larger historical level.”

All his novels, Mr. Styron once observed, focused on one recurrent theme: “the catastrophic propensity on the part of human beings to attempt to dominate one another.” He speculated in a 1982 interview that this theme found him, as a result of being a young soldier in World War II, contemplating “the forces in history that simply wipe you out”:

“You’re suddenly a cipher — you find yourself on some hideous atoll in the Pacific, and if you’re unlucky you get a bullet through your head.” He added that “within the microcosm of the Marine Corps itself, you’re just a mound of dust in terms of free will, and I think this fact of being helpless enlarges one’s sensitivity to the idea of evil.”

A native of Virginia, Mr. Styron wrote with a Southerner’s fierce sense of history — guilt over the region’s legacy of slavery, overlaid with a resentment of Yankee sanctimony. There was an elegiac tone to much of his work, a heightened awareness of loss and longing and regret.

The long shadow of William Faulkner, along with those of Thomas Wolfe and Robert Penn Warren, fell over Mr. Styron’s work, and like many members of the postwar generation, he struggled, at least initially, to come to terms with the daunting achievements of his predecessors. His prose bore the full imprint of the Southern tradition: it was lush, luxuriant, sometimes purple, and it was often put in the service of decidedly violent and gothic storylines.

From the start, a sense of melodrama informed Mr. Styron’s work, and it would thread its way through his entire oeuvre. Evil, both personal and institutional, continually stalked his protagonists, leaving them haunted by a sense of guilt and mortality — a personal apprehension, in the words of Norman Mailer, of “the gulfs and hazards that lie beneath the surface of social life.” Many of Mr. Styron’s people would turn out to be victims — of history’s random corkscrew twists, of malign social ideologies, of an individual’s pathological power games, of their own cowardice and weakness.

Mr. Styron’s debut novel “Lie Down in Darkness” (1951), a hothouse pastiche of Faulkner and Fitzgerald and Wolfe, chronicled the dissolution of a Southern family and its members’ bouts with alcoholism, madness and suicide. “Set This House on Fire” (1960), set in Italy and the United States, turned the story of a murder into a brooding, pseudo-Dostoyevskyian inquiry into the nature of guilt and salvation. And “The Confessions of Nat Turner” (1967), a fictionalized account of the slave leader’s 1831 revolt, was a “meditation on history” that explored the bloody tragedies of the era, even as it reverberated with echoes of the civil rights struggles and social upheavals of the 1960s.

As for “Sophie’s Choice,” Mr. Styron’s 1979 magnum opus about a young American writer and his friendship with an Auschwitz survivor, it opened out into a harrowing meditation on the destruction of innocence. The novel was constructed around two intertwining story lines. The first recounted the story of the tormented Sophie, the survivor who was forced to make an impossible choice: decide which of her two children would go to the gas chambers and which would have a chance to live.

The second story line recounted the story of Sophie’s neighbor, a young Southern writer named Stingo, who was based on the author’s own younger self. Sophie would initiate Stingo into a knowledge of the world; he would acquire an intimate apprehension of evil and its terrible imprint on one woman’s life, and in doing so, come to some acknowledgment of his own family’s complicity in the racial crimes of the South.

The sections of “Sophie’s Choice” dealing with Stingo’s coming of age — his harried and sometimes comical literary apprenticeship, his emotionally fraught sexual awakening — were the most keenly observed parts of the book, and in many respects, the most persuasive, avoiding the grandiosity that sometimes afflicted his work. Instead they left us with a classic portrait of the artist as a young man while reminding us just how strong the autobiographical impulse was in Mr. Styron’s fiction.

After his father and stepmother died, he said that “Lie Down in Darkness” was a projection of his “own sense of alienation” from his family, and the stories in “A Tidewater Morning: Three Tales From Youth” (1993), he later wrote, represented an “imaginative reshaping of real events” from his own childhood in Virginia.

In 1990, with “Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness,” Mr. Styron dropped the scrim of fiction he had used in his earlier books, and wrote openly about the suicidal depression that overtook him in 1985. He wrote about feeling a sense of foreboding. He wrote about being unable to write. He wrote about seeing the kitchen knives as a suicide’s tools and the garage as a place to inhale carbon monoxide. He wrote about entering a dark, Dantean wood of madness and somehow emerging intact at the end.

Although Mr. Styron’s ouevre seems somewhat slender in retrospect, each of his major novels built upon its predecessor’s achievements, working variations on earlier ideas, while amplifying them through the echo chamber of history. Mr. Styron observed after “Sophie’s Choice” that he no longer saw a writer’s career as “a series of mountain peaks” but rather as a “rolling landscape” with vistas perhaps less spectacular, yet every bit as resonant as those “theatrical Wagnerian dramas with peak after peak.”

No comments:

Post a Comment